“Widely acclaimed as the greatest writer-director-producer of the Golden Age of Radio, Norman Corwin commanded a devoted following throughout his years at CBS. He perfected his own unique recipe for success: begin with the human mind and kneed gently; add a dash of poetry, wit and wonder; to this, add a cup of raw passion and stir vigorously; garnish with sound effects, and allow one half hour to marinate in a musical score. Finally, season liberally with intelligence and digest slowly.” –Excerpt from the Program Guide to Centennial, the 10-CD Norman Corwin box set released by Radio Spirits in 2010, the 100th anniversary of his birth.

“Widely acclaimed as the greatest writer-director-producer of the Golden Age of Radio, Norman Corwin commanded a devoted following throughout his years at CBS. He perfected his own unique recipe for success: begin with the human mind and kneed gently; add a dash of poetry, wit and wonder; to this, add a cup of raw passion and stir vigorously; garnish with sound effects, and allow one half hour to marinate in a musical score. Finally, season liberally with intelligence and digest slowly.” –Excerpt from the Program Guide to Centennial, the 10-CD Norman Corwin box set released by Radio Spirits in 2010, the 100th anniversary of his birth.

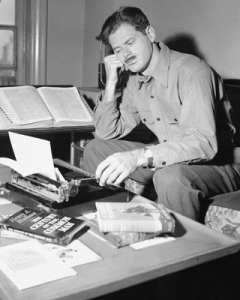

Norman Lewis Corwin was born in Boston on May 3, 1910. At an early age young Corwin developed an affinity for the written word, especially poetry. He thrilled to the words and rhythms of Byron, Keats and Whitman. It would prove instrumental in his move into radio.

Following high school, Corwin lied about his age and secured a job as a reporter for the Springfield Republican, a leading Massachusetts newspaper. He reported on human-interest stories and happily promoted a man who claimed to be the world’s fastest “ash can roller.” When the newspaper acquired a regular slot on WBZA to broadcast the news over radio, Corwin assumed the role of on-air talent.

Aware that WBZA was in need of content to fill unsold airtime, Corwin proposed a poetry series called Rhymes and Cadences. Now the writings of Byron, Keats and Whitman danced on the ether courtesy of the voice of Norman Corwin. Within a few years Corwin would recreate the show in New York City on WQXR as Poetic License. It was as a result of this series that William B. Lewis, the vice president of programming at CBS, discovered Corwin’s work and invited him to join CBS. He was not yet 28-years-old. In December 1938, CBS premiered Norman Corwin’s Words Without Music. Essentially a rebirth of Poetic License, Corwin was given free rein, a luxury afforded to few. The fourth week of the series landed on December 25, 1938. For this occasion, Corwin wrote his first original radio play The Plot to Overthrow Christmas. The rhymed play earned Corwin a few fans, notably CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow.

Corwin’s next original script was quite different in content and tone. Enraged by Vittorio Mussolini’s description of dropping bombs onto Ethiopians and calling it a beautiful sight, Corwin wrote They Fly Through the Air with the Greatest of Ease. Broadcast February 19, 1939, the program was dedicated to “all aviators who have bombed defenseless civilians.” They Fly Through the Air was promptly rebroadcast on the prestigious Columbia Workshop. Time magazine announced Corwin’s “bid for a front-row seat among radio poets.”

Corwin’s profile increased at the network. He wrote, directed and produced the series Seems Radio is Here to Stay, and then helmed The Pursuit of Happiness, hosted by Burgess Meredith. He continued to write and direct for The Columbia Workshop, Forecast, The Cavalcade of America and The Gulf Screen Guild Theater.

In 1941, Corwin was offered twenty-six consecutive weeks on The Columbia Workshop. Under the prestigious title 26 By Corwin, he would write a new script each week, have its musical score composed, cast and rehearse the show, and direct the live broadcast for six uninterrupted months. 26 By Corwin allowed his artistry full expression. Programs included musicals, fantasies, dramas, satires, and Biblical stories. Corwin’s poetic language and progressive world-view combined to set him even further apart from his contemporaries. Yet CBS decided not to offer Corwin a new contract. He was, in essence, fired.

His unemployment would not last long. William B. Lewis, the man who had hired Corwin in 1938, now worked for the government’s Office of Facts and Figures. A significant anniversary was on the horizon that the Roosevelt administration sought to exploit by joining all four national radio networks together (CBS, NBC-Red, NBC-Blue, and Mutual) for a single program celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights on December 15, 1941. Lewis knew of only one man to write, direct and produce this historic broadcast: Norman Corwin. Still stung from his CBS departure and tremendously fatigued from the grueling 26 by Corwin series, he nevertheless accepted the challenge and, with only four weeks to spare, began his research in the Library of Congress.

Corwin was still writing the show, We Hold These Truths, on December 7, 1941, when word came that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Now at war, Corwin had stars lining up to be a part of this patriotic program. James Stewart headed a cast that included Edward G. Robinson and Orson Welles. Originating from Studio A at KNX Los Angeles, the program switched to Washington so President Roosevelt could speak. Leopold Stokowski conducted the New York Philharmonic Orchestra playing The Star Spangled Banner to conclude the show. We Hold These Truths won Corwin the Peabody Medal.

CBS immediately resigned Corwin just as the government asked him to oversee the four-network series This is War! Corwin agreed, even writing and directing several of the shows himself. Although great writers such as Archibald MacLeish and Stephen Vincent Benét contributed scripts, the series was little more than government-sponsored propaganda. Corwin was happy to move on to projects where he could better control the content.

In June 1942, Corwin flew to England for An American in England. Edward R. Murrow produced the joint CBS-BBC venture. Corwin’s mission was to explore wartime England and report back about what he observed. The show was short-waved from secret BBC facilities. Corwin returned to America after the final show.

Continuing his labors on behalf of the war effort, in 1943 Corwin wrote, directed and produced another CBS-BBC series, Transatlantic Call. He also wrote and directed the audition program for Passport for Adams, starring Robert Young as a reporter who travels to Allied nations.

It wasn’t until 1944 that Corwin returned full-force to the format which best displayed his work. From March to August of 1944 Corwin was again given control of The Columbia Workshop. Under the title Columbia Presents Corwin, Corwin wrote pieces that allowed him to take the listener anywhere his own muse led him. The series returned for eight weeks in 1945.

With the war in Europe winding down, CBS asked Corwin to prepare a one-hour special for the day of victory. The resulting program was, without a doubt, Corwin’s masterpiece: On A Note of Triumph. On Tuesday, May 8, 1945, at 7pm Pacific War Time, Corwin threw his finger to cue the start of the program. Martin Gabel served as the listener’s guide on a journey through past and present, while peering into an uncertain future. Response to the show proved so overwhelming that CBS asked for a repeat performance five days later, on Sunday, May13th. Carl Sandburg called it “one of the all-time great American poems” and Time magazine proclaimed it “U.S. radio at its best.”

With the war in Europe winding down, CBS asked Corwin to prepare a one-hour special for the day of victory. The resulting program was, without a doubt, Corwin’s masterpiece: On A Note of Triumph. On Tuesday, May 8, 1945, at 7pm Pacific War Time, Corwin threw his finger to cue the start of the program. Martin Gabel served as the listener’s guide on a journey through past and present, while peering into an uncertain future. Response to the show proved so overwhelming that CBS asked for a repeat performance five days later, on Sunday, May13th. Carl Sandburg called it “one of the all-time great American poems” and Time magazine proclaimed it “U.S. radio at its best.”

Corwin had very little time in preparing a similar program to celebrate V-J Day. Simply titled 14 August, Corwin wrote this overnight for Orson Welles to perform. The script contained only one sound effect. Nevertheless, the program proved a worthy summation of the costs of war and the high price of freedom.

In 1946, Corwin was selected as the first recipient of the Wendell Willkie One World Award. Willkie, the Republican challenger to FDR in 1940, visited American allies across the globe in 1942. In his best selling book, One World, Willkie posited that international cooperation was the only way to solve future problems. After his death in 1944, friends established The One World Award with the purpose of retracing Willkie’s famous trip in his honor.

Corwin traveled to 17 countries, covering 37,000 miles. He interviewed heads of state as well as people on the street, asking them what they thought of present postwar conditions. These recordings served as the basis of Corwin’s final series for CBS, One World Flight.

Corwin traveled to 17 countries, covering 37,000 miles. He interviewed heads of state as well as people on the street, asking them what they thought of present postwar conditions. These recordings served as the basis of Corwin’s final series for CBS, One World Flight.

William S. Paley, the head of CBS, asked Corwin to broaden the appeal of his shows. Corwin knew he was being asked to dumb down his approach. Not surprisingly, the next contract he was offered contained onerous provisions that Corwin could not accept. After ten years, Norman Corwin and CBS parted ways.

In response to the growing influence of the House Un-Americans Activities Committee, Corwin agreed to write and direct Hollywood Fights Back in late 1947. He brought to the microphone Judy Garland, Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, William Wyler and others, warning of the consequences caused by the committee’s reckless investigations. When the infamous booklet Red Channels was published, Norman Corwin was one of the 151 names listed. Work offers were sparse. Some projects dried up completely. The fact that Corwin had never been a Communist was immaterial. He was liberal, and therefore, a threat.

Corwin persevered. As head of Special Projects at United Nations Radio, Corwin continued his dedication to the virtues of freedom, human rights and international cooperation. His first U.N. show, Could Be, ponders a future where governments attack the problems of famine and disease with the same zest and resources they apply to making war. One of its listeners wrote to Corwin, “I wish to congratulate you on one of the best radio dramatizations that has ever been my good fortune to hear, and I wish not only every American, but all foreigners, could hear it.” The letter was signed by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

By 1952, Corwin departed U.N. Radio and turned to writing books, essays, stage plays and screenplays. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay of the 1956 film Lust for Life. Corwin’s play about the Lincoln-Douglas debates, The Rivalry, ran on Broadway in 1959 and has had numerous revivals, including a 2010 production at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC. His next play, The World of Carl Sandburg, starring Bette Davis, also made it to Broadway.

In addition to penning more screenplays, Corwin wrote books such as Overkill and Megalove (1963), Holes in a Stained Glass Window (1978), Trivializing America (1983), Norman Corwin’s Letters (1994), and One World Flight: The Lost Journal of Radio’s Greatest Writer (2009). His final book, Memos to a New Millennium: The Final Radio Plays of Norman Corwin was published posthumously in early 2012.

In 1969 Corwin wrote Prayer for the 70s especially for Eddie Albert to deliver on the Ed Sullivan Show. It proved so popular that Albert retuned later in 1969 for a second reading. A limited edition book was also published.

In 1971 Corwin was invited to produce a television series for syndication by Westinghouse. Norman Corwin Presents aired 26 episodes in 1971-72. Some were updated adaptations of his classic radio shows such as The Undecided Molecule starring Milton Berle. One was a revised version of his 1964 stage play The Hyphen, now titled The Discovery (both starring William Shatner). The Pursuit episode starring David McCallum was a powerful original work for the series. Other writers and directors contributed to the series as well. In addition to the talents of Berle, Shatner, and McCallum, episodes also featured Donald Sutherland, Leslie Nielsen, Forrest Tucker, Cicely Tyson, Michael Dunn, Beau Bridges, Alan King, Fred Gwynne, Lorne Greene, Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, and Brock Peters.

Corwin retuned to radio in tiny steps. In 1979 he wrote and directed an episode of the Sear Radio Theater called The Strange Affliction starring Nanette Fabray. In 1983 he was asked by National Public Radio to create new pieces celebrating American holidays. He responded with six shows examining Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Thanksgiving, and New Years Day. It was just the beginning of his association with the network.

Corwin retuned to radio in tiny steps. In 1979 he wrote and directed an episode of the Sear Radio Theater called The Strange Affliction starring Nanette Fabray. In 1983 he was asked by National Public Radio to create new pieces celebrating American holidays. He responded with six shows examining Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Thanksgiving, and New Years Day. It was just the beginning of his association with the network.

In 1995 Corwin wrote Fifty Years After 14 August, narrated by Charles Kuralt, followed by a new series for NPR titled More by Corwin. These new 60-minute shows reaffirmed Corwin as the master of the art form. No Love Lost starred Jack Lemmon, Lloyd Bridges and William Shatner; The Writer with the Lame Left Hand starred Charles Durning; The Curse of 589 starred William Shatner, Samantha Eggar and Carl Reiner; Charles Kuralt narrated Our Lady of the Freedoms just before his death; The Secretariat starred William Shatner along with Hume Cronyn. The final entry in the series aired on December 31, 1999: Memos to a New Millennium, and was narrated by Walter Cronkite.

In 2005 We Hold These Truths (1941) was added to the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry along with Neil Armstrong’s Apollo 11 transmissions for the moon, MacArthur’s “Old Soldiers Never Die” speech to Congress, and Edward R. Murrow’s broadcasts for London during the Blitz.

The following year the film A Note of Triumph: The Golden Age of Norman Corwin won the Oscar for best short documentary for 2005. It was directed by Eric Simonson and produced by Corrine Marrinan.

Norman Corwin also began a distinguished teaching career in the 1960s, taking him to Idyllwild, UCLA and finally USC, where he remained on faculty until the day he died.

Norman Corwin continued to write in his later years and remained an active champion for the ideals he had always cherished. A proud and sometimes critical American, Norman Corwin stood firm in his convictions. He passed away at his home in Los Angeles on October 18, 2011. He was 101 years of age.

On April 13, 2022, the Library of Congress National Recording Registry announced that it had selected “On a Note of Triumph” as one of the 25 significant sound recordings to be preserved in 2022. Also included are in the induction are WNYC’s coverage on 9/11, FDR complete presidential speeches, Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, and music from Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Queen, Journey, Alicia Keys and others.